An Annotated Bibliography of Global and Non-Western Rhetorics: Sources for Comparative Rhetorical Studies

Edited by

Anne Melfi, Nicole Khoury, and Tarez Samra Graban

With contributions authored by

Brian Adam, San Jose State University

Leonora Anyango, Community College of Allegheny County

Tyler Carter, Duke Kunshan University

Lance E. Cummings, University of North Carolina at Wilmington

Stephen Kwame Dadugblor, University of Texas at Austin

Rasha Diab, University of Texas at Austin

Dan Jerome Dirilo, San Jose State University

Tarez Samra Graban, Florida State University

Elif Guler, Longwood University

Nicole Khoury, University of California, Irvine

Uma S. Krishnan, Kent State University

Keith S. Lloyd, Kent State University at Stark

Abbie McGarvey, San Jose State University

Anne Melfi, Independent Scholar

Michael Pfirrmann, San Jose State University

Amanda Presswood, Florida State University

Maria Prikhodko, DePaul University

Alexis Rocha, San Jose State University

Jason Sharier, Kent State University at Stark

Amber Sylva, San Jose State University

Erin Cromer Twal, Embry Riddle Aeronautical University

Saveena (Chakrika) Veeramoothoo, University of Minnesota, Twin Cities

Ben Vevoda, San Jose State University

Xiaobo Wang, Sam Houston State University

Hui Wu, University of Texas at Tyler

Michelle Zaleski, Marymount University

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the members of the Global & Non-Western Rhetorics Standing Group of the Conference on College Composition and Communication (CCCC), who, in 2016, began to crowd-source one central bibliography, from which we drew many of the sources that have been annotated here. Since that time, development and completion of this bibliography have been a community effort. We wish to thank graduate students in the History of Rhetoric graduate seminar at San Jose State University who contributed entries to developing the bibliography. In addition to the contributors listed above, who coauthored many of our over 200 entries, the editors are grateful to Iklim Goksel, Arabella Lyon, LuMing Mao, Priya Sirohi, Adnan Salhi, Shakil Rabbi, Ryan Skinnell, and Liz Angeli and Matt Cox for their enthusiastic support of this project.

Introduction

I. Re/Defining the Historical Moment

The “Annotated Bibliography of Global and Non-Western Rhetorics” bears witness to a robust literature that is not so much new as it has been emerging for several decades under one of several monikers: “comparative,” “global,” and/or “non-Western.” At the same time, this particular project emerges at the intersection of two recent conversations that reflect a need to look deliberately and categorically at how the monikers have evolved.

The first conversation occurred at the 2013 Rhetoric Society of America biennial Institute, where participants of the “Comparative Rhetoric” seminar produced a Manifesto that offered a blueprint for comparative rhetorical work in the current historical moment, revisiting its operational definition(s), considering its (new) objects of study, articulating its critical goals, and reflecting on its variant methodologies. The 2013 Manifesto, and subsequently its 2015 publication in Rhetoric Review, made several disciplinary assertions: that comparative rhetoric could be defined as a rhetoric that “examines communicative practices across time and space by attending to historicity, specificity, self-reflexivity, processual predisposition, and imagination”; that the objects of its study “have significant ethical, epistemic, and political orientations,” including practices originating in non-canonical texts or practices that “have often been marginalized, forgotten, dismissed . . . and/or erased altogether”; that one of its principal goals is to “embrace different ‘grids of intelligibility’ or different terms of engagement for opening new rhetorical times, places, and spaces”; and that its principal methodology includes “the art of recontextualization characterized by a navigation among and beyond the meanings of the past and the questions of the present; what is important and what is merely available” (“Symposium,” 273–274).

Several years later at the 2017 RSA biennial Institute, the workshop re-convened under Mao’s and Lyon’s leadership, with the playfully constructed title “‘The Rest of the World’: Recognizing Non-Western Rhetorical Traditions,” calling into question, among other things, which vantage points would reflect “the west” versus “the rest.” Workshop participants discussed strategies for translation work, and the consequent implications of recontextualizing rhetorical cultures. They considered nuanced distinctions between cultural and comparative rhetorical methodologies, including how to operationalize space and place for each methodology. They discussed complications to the kinds of moral- and value-shifting that are inevitable for intercultural scholarship. And finally, they reflected on the growing popularity of foundational compilations of secondary scholarship on Non-Western/global rhetoric since the turn of the millennium—such as Lipson & Binkley, eds. Ancient Non-Greek Rhetorics and Rhetoric Before and Beyond the Greeks; Borrowman, Lively, & Kmetz, eds. Rhetoric in the Rest of the West; and Baca & Villanueva, eds., Rhetorics of the Americas; alongside special issues of College English, Rhetoric Society Quarterly, and College Composition and Communication—and their appearance on an increasing number of graduate and undergraduate syllabi.

The second conversation occurred with the resurgence of the Non-Western/Global Rhetorics Special Interest Group at the Conference on College Composition and Communication, and its subsequent reorganization as a CCCC Standing Group,1 which helped identify a strong and immediate community of scholars whose expertise as students or instructors of global rhetorical approaches merited an outlet for collaboration. Originally offered from 2008 to 2011, this SIG began as a non-Western SIG focused on scholarship of Middle Eastern Rhetorics, but soon evolved into a space for considering the study, analysis, and codification of rhetorical practices of different nations and civilizations. After some years on hiatus, at the well-attended resurgence of the SIG in 2015, participants realized it might be time to establish a new and ongoing mission for the group.

Two groups formed at that point: (1) one under the aegis of “non-Western” rhetorics, which would encompass work in Middle East studies, but was also concerned with other geographical areas that lie outside the boundaries of a purely Western hegemony; and (2) the Arab American Caucus, focusing on cultural identity or a specific research area addressing Arab, Muslim, and Arab American issues. Inspired by George Kennedy’s definition of “Comparative Rhetoric” as “the cross-cultural study of rhetorical traditions as they exist or have existed in different societies around the world” (Comparative, 1), as well as LuMing Mao’s later call to “renounce [Western] domination, adjudication, and assimilation, and . . . nurture tolerance, vagueness, and heteroglossia” (“Reflective,” 418), the Non-Western/Global Rhetorics SIG aimed to bring together emerging and established scholars in history, theory, and pedagogy who were interested not only in how rhetorical traditions varied in different parts of the world, but also how they have been realized, circulated, or accessed, and how they might be better understood, apart from a purely Western/non-Western binary.

The realization that individual members of this group—now the Global & Non-Western Rhetorics (G&NWR) Standing Group—would benefit from a more horizontal distribution of their principal texts and approaches to teaching global rhetorics helped identify the Annotated Bibliography as a convenient and expedient genre for diversifying our pedagogical traditions. Specifically, from 2016 through 2019, leadership of the SIG expanded to involve scholars of African, Ancient Egyptian, Arabic, Chinese, Indian, Islamic, Japanese, Jewish, Korean, Russian, and Turkish rhetorical traditions—as well as scholars working more broadly on intercultural rhetorical issues—and it was in that moment of expansion and pedagogical need that we opted to build out the crowd-sourced bibliography into its more robust annotated and published form. We had heard expressed time and again through our meetings and across our listservs a desire to promote resources that not only included and articulated, but also questioned, a range of global rhetorical theories, practices, and pedagogies.

What we heard expressed was the need for a concise compendium of global rhetorical resources that offered new avenues for studying and teaching communication in postcolonial and decolonial contexts, and around which we could build or revitalize our curriculum. That need has fast been reinforced by the emergence of newer scholarship, including Global Rhetorical Traditions, edited by Hui Wu and Tarez Samra Graban, an anthology of critical commentaries and translated primary sources of Non-Western rhetorical traditions and practices, and most recently the work of 43 scholars in Keith Lloyd’s edited collection, The Routledge Handbook of Comparative World Rhetorics. By all respects, and in every way, conversations between and among the comparative, the global, and the non/Western are moving more quickly than they can be captured here.

Those conversations have been buoyed by countless others. Since its first Congress in 1977, the International Society for the History of Rhetoric has not only gathered together the voices of international and multilingual scholars, it has also posed challenges to dominant scholastic perspectives, and done so more actively since its inclusion of African, East Asian, and South Asian scholars and panels. Beginning in 1997, the Feminisms and Rhetorics Conference, co-hosted by the Coalition of Feminist Scholars in the History of Rhetoric and Composition, has welcomed global perspectives and “alternative” rhetorical histories and traditions. And since its first conference in 2007, the African Association for Rhetoric has made an intellectual home for both pan-African scholars and teachers of rhetoric across the disciplines and for scholars with an exclusive interest in pan-African rhetorical perspectives and methodologies. These reflect only a few of what we recognize as an increasing number of global pathways to collaboration on comparative rhetorical work. In addition, members of the G&NWR Standing Group already report an increase in curricula and course material that engage with global and non-Western rhetorical studies both within the U.S. and abroad. Other organizational initiatives, such as “Wikipedia Project: Writing,”2 encourage contributions by a range of scholars and students alike, offering a testament to the shared responsibility of reading historical contributions to rhetoric that have been largely ignored and of challenging knowledge that shapes our perceptions of the legitimacy of these very contributions.

II. Acknowledging Traditions and Establishing Trends

Categorizing such a vast field of work is a vexed activity, at best. We began by acknowledging the keystone conversations and debates out of which comparative rhetorical approaches have emerged, and these are reflected in our sections on “Introductory Overviews” and “Methodologies.” From there, we offered loosely descriptive categories that reflect language, culture, and—to some degree—the principal historical positioning of various global rhetorical practices, including African, Arabic, Chinese, Egyptian, Celtic (non-Anglo Irish), Japanese, Jewish, Korean, Near Eastern, Pre-Columbian American, and South Asian. Readers will note that these categories are broader than single language groups, yet narrower than geographical regions, and that these categories are sure to evolve.

While we do not consider the 14 categories and 207 entries that constitute this bibliography to be absolutely comprehensive of all work in the field of global rhetorical studies, we hope readers will recognize the Standing Group’s principal goals in our selections: to increase rhetorical knowledge globally; to create new kinds of collaborations; and to promote the circulation of key sources of knowledge about rhetorical practices that occur in other cultures. This includes both broadening and narrowing field definitions of “rhetoric” and “non/Western” so as to include a wide range of communicative practices beyond the Aristotelian frame without making either term overly expansive. Most importantly, however, the Standing Group and this bibliography aim to move the field’s rhetorical terminology toward demonstrating an understanding that concepts from these and other traditions are already germinal and foundational rather than “new.”

We also trust that readers understand why we cannot promise complete coverage of the “world” or absolute inclusivity of all known rhetorical traditions. In the spirit of exploration, the earliest iteration of the 2016 bibliography was organized without categorical divisions to encourage discussion among collaborators about how best to shape it (i.e., by geospace, by subtopic, by methodology, by region, by orientation, by pedagogical emphasis, etc.). At the time, contributors wanted to trouble rather than define. Ultimately, we opted to organize the bibliography according to identified rhetorical regions and to publish the strongest annotations that showed sufficient range in breadth and depth and variation of comparative approaches to each tradition. We also provided contributors with the following foci to offer our bibliography shape and scope, helping to fill what we understood to be a critical gap:

We welcomed sources that demonstrate a convergence of where rhetoric and writing studies can meet non-Western and global rhetorics—including ancient rhetorical cultures which are not necessarily based in Greco-Roman paradigms, but are founded on different premises and cultural priorities, and contemporary expressions of the above.

We welcomed sources that demonstrate the breadth and depth and variation of “comparative” rhetorical traditions—in particular, those we see occurring at the “cross-cultural” intersection, such as work that investigates histories, theories, or pedagogies growing from attempts to cross various lines or borders or traditions).

We welcomed sources that provide a more complex understanding of “comparative” rhetoric as a theory and a practice, beyond simply using western axioms to compare non-Western traditions, and even beyond simple rejections of so-called “Western” traditions.

We welcomed sources that demonstrate an active crossing-over of cultures or methodologies related to oral and written communication; in a few instances, this includes feminist rhetorical work that examines how specific cultures shape or are shaped by transnational discourses, though employing primarily comparative methodologies for the study of rhetorical cultures or demonstrating pedagogy for or within rhetorical cultures.

Finally, we welcomed sources that illustrate the ways in which rhetorical topics function across international borders, within distinct cultural contexts, and/or as sites for post- and decoloniality, especially for reviving pedagogical work.

Unfortunately, attempting to address such a critical gap through this Annotated Bibliography also involves some necessary exclusions.

We excluded sources devoted primarily to ESL, ELL, L2 or composition pedagogy, including World Englishes or the impact of English language on other cultures.

We excluded sources devoted primarily to Western fusion rhetorics (African-American, Arab-American, Chinese-American), unless such studies worked with and through comparative methods.

We excluded sources derived from comparative literary studies that do not clearly shed light on a rhetorical culture.

And we excluded sources derived from intercultural communication studies more generally, that do not shed light on the nature of particular rhetorical cultures.

Thus, across the 207 entries that constitute this first version of our Annotated Bibliography, readers may find some work that is inclusive of L2/ESL teaching and scholarship, as well as the important work of transnational composing, yet those are not our principal areas of emphasis. In future iterations of this Annotated Bibliography, we hope to include the entries that could not fit here and complicate regional orientations even further than we do. As well, ancillary to this Annotated Bibliography, the G&NWR Standing Group plans to update and circulate its crowd-sourced bibliography without annotations—one which continues to grow, and from which we will continue to draw. While the annotations are no substitute for the sources themselves (they are merely signposts, indicating the authors’ greater breadth and depth), we hope readers will use them to discern the rich contributions that each source makes to the global and non-western rhetorical conversation.

Even still, we recognize that coverage will be uneven, and this is in part due to the dual function of the Bibliography. That is, it serves both as a crash course or introduction to scholars just now delving into the field, and as a gathering of insights for those already looking to problematize, question, rethink, or pursue the field’s prior assumptions. For example, a proliferation of foundational and persistent scholarship in the past two decades on Chinese rhetorics means that a good number of our contributors, even if they are not principally Chinese rhetoric scholars, could contribute to that category.3 Furthermore, among the three editors of this version, our collective strengths lie in comparative methodologies as well as African, Arabic, and South Asian rhetorical traditions, which may explain why those traditions have received more attention. In expanding our South Asian category, in particular, we hope to provide access to more scholars who wish to explore that field. Sue Hum and Arabella Lyon have observed that the prior dearth of publication on the rhetorics of South Asian cultures has made it difficult for one to find a starting point (“Recent” 161). We can and do extend this observation to a number of traditions in this Bibliography, and thus encourage our readers to consider each tradition as merely a “starting point.”

III. Two Critical Interventions

Given the dual function of this Annotated Bibliography—to serve as both introduction and interrogation—its organization is not only practical, it also signals a commentary on two critical interventions we hope to make in our field. First, in naming rhetorical regions, we propose a hybridized organizational model for global rhetorical studies that both offers a regional and geographic organization (African, the Americas, Chinese, Japanese, Korean), and features linguistic (Arabic, Celtic), cultural (Egyptian, South Asian), and religious (Jewish) sections to show the complexity and hybridity of this field. That is, in differentiating the myriad cultural differences within what have historically been understood as large language groups, we hope to challenge long-held assumptions about language and tradition in non-Western rhetoric and global rhetorical studies by employing a set of categories (or rhetorical regions) that are not wholly uniform. Second, in using tags to foreground various themes that cut across rhetorical regions, rather than to delimit the dominant conversations about each region, we hope to trouble static conceptions of how language, rhetoric, and communication function within each region.

Naming Rhetorical Regions

For the editors and contributors of this Annotated Bibliography, naming is less an act of epistemic declaration than it is a courting of particular traditions and an attempt to make those traditions more available for teaching and study. We first noted the need for a hybridized naming schema while planning the un-annotated version of this bibliography. When contributors suggested entries for annotation, they did so according to the organizational schemas that had served them as inroads to understanding comparative rhetorics. A set of geographical categories emerged as a natural starting place because we could name as many geographical areas as we needed in order to signify cultural, ethnic, and even linguistic groupings reflected in their suggestions. However, we wanted the categories to reflect the breadth and depth of explicitly global and cross-cultural rhetorical studies; thus, once contributors finished their work, we condensed over 25 categories into 14, inviting more contributions in areas where coverage was thin, or inviting further clarification from new students and seasoned scholars alike on how to optimally recognize the various ways in which a single tradition might be categorized, knowing ultimately that we could rely on the tagging feature of PresentTense to cross-list as much as was necessary. In doing so, we hoped to lay the groundwork for an inclusive naming practice.

Ideally, our named regions would function as linguistic and cultural hybrids, and we recognize that this marks a simultaneous reliance on, and departure from, some of the field’s core organizational logics. In some respects, we follow the same logic guiding Lipson and Binkley’s Rhetoric Before and Beyond the Greeks and Ancient Non-Greek Rhetorics, in which they include geographic areas while pointing out the importance and contribution of each area to its scholarship. Specifically, they identify six civilizations occurring between 5000 and 1200 BCE—Middle East; Egypt; the Indus Valley; China; Mesoamerica; and the two Andean civilizations—but acknowledge that the book deals with only three (Rhetoric, 4). Moreover, they make distinctions among Near Eastern cultures, organizing them further according to time and place, such as with Mesopotamian and Egyptian, and they draw attention to religion as a viable category when there is a distinct body of work, such as with Biblical Rhetorics (17). They also distinguish alternative Greek rhetorics, such as Rhodian, and end with “Suggestions for Teaching Ancient Rhetorics.” We do some of the same things in our Annotated Bibliography, entertaining both ancient and modern, intra-cultural and intercultural, and theoretical and practical.

However, where we differ from Lipson and Binkley’s approach is in adopting a categorical framework that invites a critical questioning of regionalism and regional identifications. In other words, we utilize—even capitalize on—the problem of delineating traditions. In retaining several geographic sections, as well as featuring non-regional sections, and using the tagging feature to mark complexities, we are able to offer a representation of the flexibility and complexity of the work that is featured in global and Non-Western rhetorical studies by making visible the discrepancies in naming. For example, we included an Arabic Rhetoric category to distinguish the research on Arabic rhetorical tradition which was not tied to one geographic location, but rather associated with religion and emerging from within different cultural historical contexts, such as the Greco-Arabic Translation Movement in Baghdad (see more discussion of how we organized tags to identify specialized categories).4 This movement is largely made up of non-European commentators on Aristotle’s works, and could serve as part of the Western tradition; however, as a result of our deeply held assumptions about the dominance of Aristotelian logical thought that forms the foundation for Western rhetorical tradition, we have incorporated these contributions under “Arabic Rhetoric” to better reflect how the contributions of some Arabic rhetorical theorists are still understudied, if not ignored (Borrowman 98).

Arabic Rhetorics aren’t the only complicating category.5 The problem of delineating traditions can be further illustrated in the case of Egypt because it marks a set of traditions rhetorically and culturally different from other Arabic languages and groups and because of the formation of the tradition we know as Ancient Egyptian rhetoric. Recent work on Egyptian rhetoric demonstrates Egyptian rhetorical tradition has different assumptions about language, communication, and the individual from Arabic rhetorical tradition, as evidenced in the principles of maat that served as principles of governance in Africa (Blake) and organized Ancient Egyptian life (Lipson). Distinguishing between Egyptian and Arabic rhetorics urges us to think differently about how we categorize and organize linguistic and cultural markers on global, cultural, and rhetorical traditions. For example, while Edward Said’s “Living in Arabic” describes the particular use of standard Arabic and dramatic delivery in political speeches of Palestinian and Egyptian leaders, we locate this annotation in “Arabic Rhetoric” and not “Egyptian Rhetoric” for two reasons: first, because Said narrates his own personal experience living in Arabic-speaking countries and learning classical and colloquial Arabic; and second, because the “Egypt” categorization in this Bibliography includes entries that primarily address the rhetorical traditions of Ancient Egypt.

Tagging as Troubling

We further use tagging in both practical and critical ways. Practically speaking, the tags that follow each annotation identify themes that are present, as well as themes which can cut across the broad categories, mostly geographical, into which we have organized the literature; such categories as Chinese, South Asian, or African can hardly represent the great diversity of themes that come into play in the discourse on global and Non-Western rhetorics. However, the tags also serve to identify not only the themes that cross cultures, but those that emerge as importantly present within a culture, a methodological approach, or a theory, some of which have not been a significant part of the conversation in rhetorical studies. Thus, tagging is an integral part of this project, as it serves to foreground various threads and themes of scholarship currently lively in the discourse of this nascent field, and to aid scholars who are seeking unresolved avenues of inquiry.

Following Arabella Lyon in her aptly named “Tricky Words,” we felt this tagging should reflect our shared “attempt to understand new cultures” and not merely serve as “an extension of what we already know” (Lyon 243)—i.e., forcing “square pegs into round holes” (Mao 213)—or an attempt to prescribe the themes best suited to covering diverse rhetorics still coming to light in our emerging field. Thus, we employ tagging as an “attempt to engage concepts, beyond [our] discipline” (Mao 244), and to recognize what LuMing Mao calls the “importantly present” (216). Walking a narrow line between latent categories and emergent ones, we have privileged tags that have emerged from the critical (often unfamiliar) vocabulary of the material itself, so as to best represent the topics and themes offered there.6 Like our named regions, this list, too, defies a parallel structure, yielding terms such as harmony, indirection, moksha, nommo, and ritual—tags which have not been a significant part of the conversation in Western rhetorical studies—alongside more familiar terms such as rhetorical silence, persuasion, deliberative rhetoric, invention, and logic.

In sum, knowing that both “Western” and “Non-Western” are “politically motivated construct[s],” knowing that we cannot approach the cultural and heterogeneous linguistic practices of all cultures by foregrounding Western assumptions, and knowing that we must work against efforts to “distort and colonize an alternative understanding revolutionary to Western rhetoric” (Hum and Lyon 157), we settled for naming categories and archival tags that do not all operate uniformly but rather make visible some categorical tensions. We tried to think historiographically about how, in this moment, the named traditions could be valued as distinct while also employing tags to demonstrate their categorical mobility.7

IV. Future Directions

Given the coevality of the many aspects underlying global rhetorical traditions (including, but not limited to antiquity, geography, language, and duration), we and the 26 contributors to this Annotated Bibliography take seriously the need to “frequent places where rhetoric is unrecognized, or is evidenced only by barely acknowledged traces or gaps” (Mao and Wang, “Symposium” 241). In its ideal form, this Annotated Bibliography would offer as many representations of non-Western rhetorical traditions as possible. Yet, recognizing potential criticism of reductionism, scopism, or “rhetorical accommodationism” on our work (O’Mally, “Not”), we offer this Bibliography simply as a reflection of selected key critical developments in what is not strictly Euro-American rhetorical study, tapping into several traditions that we know are being noticed, identified, and opened up as having richer alternative sources for their own historical study. Moreover, we offer this Bibliography as a representation of what is now made possible through comparative rhetorical epistemologies, which need not function only within binary associations, and our contributors help us to witness the types and kinds of traditions that challenge such binaries toward noticing an expanded range of critical possibilities.

We initially wanted this first publication of the Annotated Bibliography to offer starting points for scholars interested in global rhetorical studies, not necessarily comparative. However, as contributors submitted entries for consideration, it continued to grow in several directions. As a result, several entries that do not appear in this version of the bibliography have already been slated for the second edition. For example, in spite of the fact that two of our editors’ scholarship lies within the area of transnational feminist rhetorics, the adequate development of such a category would call into question national and international policies, politics, narratives, and local cultural definitions—all questions that we felt needed more attention than the first edition of this project could reasonably offer. As a result, we chose to exclude Gloria Anzaldua’s Borderland, Shireen Hassim’s “Nationalism, Feminism and Autonomy: The ANC in Exile and the Question of Women,” Saba Fatima’s “Muslim-American Scripts,” and Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s “How Do We Write, Now?”

In other cases, we chose to retain the entries in the Bibliography, but to disperse them among various categories, knowing they would be better served not in a section on transnational feminism, but in one or more separate categories where they could be framed in terms of the global rhetorical tradition from which they emerged or to which they contributed, for example pre-Columbian American, Palestinian, Muslim, and/or Chinese. Moreover, they were also tagged as “feminist rhetorics” for easy identification. Readers can expect that, as this Annotated Bibliography project evolves, some categories will move into and out of clear delineation according to the religious, geographic, and cultural issues that they evoke.

V. Conclusion

We have acknowledged that the call for rhetorical studies to globalize their focus is not a new one, although we do still anticipate a radical recentering of college and university curricula so that global becomes a driving force rather than an additive or an inclusion, and so that Western reveals both indigenous and exogenous claims. As we remain aware of how our recentering continues to shape power imbalances both in our scholarship and in our classrooms, we need to foreground our curricula by further asking our students to examine their own work, help them acknowledge and examine their own assumptions and beliefs, and “incorporate self-reflexive practices to open up new spaces for writing and creating knowledge” (Khoury 172). These new areas of inquiry ask us to reach beyond our borders and edges, and this work poses “particularly high hurdles” for scholars trained in Rhetoric and Composition due to a lack of specialization in languages and civilizations of non-Western ancient cultures within their academic programs (Lipson 4), which takes time to fully achieve.

In the meantime, we suggest that readers approach this Annotated Bibliography with a feminist lens, raising questions about how such projects contribute to the re/formation of intellectual landscapes, and reflecting critically on how they read, interpret, understand, evaluate, and value alterity. The feminist rhetorical work of “rescue, recovery, and (re)inscription” has given our field a deeper and richer understanding of underreprented rhetors throughout history (Royster and Kirsch 31). However, as we move past the emergence of rhetorics grounded in just these three approaches, we see that the “edges” that inform this intellectual landscape become more deeply etched (Royster and Kirsch 43). Like most work in non-Western and global scholarship, the real strength of feminist scholarship lies not in the promotion of a particular landscaping practice, but in the implicit interrogation of its foundational assumptions. If this Annotated Bibliography can be of use to contemporary rhetorical scholars, rhetorical historians, cultural rhetoricians, and/or comparatists, let it be for facilitating the closer examination of texts within their historical, cultural, and linguistic frameworks, and for promoting descriptive analysis of these texts, rather than for drawing revisionist conclusions about them.

Navigation

Introductory Overviews

Methodologies

African Rhetorics

The Americas (pre-Columbian American)

Ancient Egyptian Rhetorics

Arabic Rhetorics

Celtic (non-Anglo Irish) Rhetorics

Chinese Rhetorics

Japanese Rhetorics

Jewish Rhetorics

Korean Rhetorics

Near Eastern Rhetorics

Pedagogy for Global/Non-Greek Rhetorics

South Asian Rhetorics

Tags

Aesthetics

Afrocentric Rhetorics

Al-Farabi

American Writing Pedagogy

Analects

Analogy

Ancient Rhetorics

Archaeology

Argumentation

Aristotle

Asiacentric Rhetorics

Audience

Averroes

Biblical Rhetorics

Celtic Rhetorics

Chancery Writers

Chinese Rhetorics

Chinese Women Writers

Citizenship

Classical Chinese Rhetorics

Colonial Rhetorics

Communication Theory

Comparative Rhetoric

Confucius

Consciousness

Consensus

Contact Zone

Contrastive Rhetoric

Cosmology of Speech

Cross-Cultural Rhetorics

Cultural Rhetorics

Dao/Tao

Debate

Deliberative Rhetorics

Delivery

Democratic Rhetorics

Dialogue

Diasporic Rhetorics

Didactic Rhetorics

Discourse Analysis

Divinity of Speech

Drama

Egyptian Rhetorics

Eloquence

Emotion

English Language

Enthymeme

Epics

Epideictic

Epistemology

Epistolary Rhetorics

Essay Genre

Essentialism

Ethics

Ethnography

Exegesis

Feminist Rhetorics

Fieldwork

Gendered Rhetorics

Genres

Governance

Greek Rhetorics

Guiguzi

Han Feizi

Harmony

Heart

Hindu Rhetorics

Historiography

Human Rights

Hybridity

Identity

Ideology

Imperialism

Indian Communication Theory

Indian Rhetorics

Indigenous Rhetorics

Indirection

Intercultural Communication

Invention

Islamic Rhetorics

Japanese Rhetorics

Jewish Rhetorics

Justice

Kenneth Burke

Latin American Rhetorics

Legalism

Levels of Speech Theory

Linguistics

Logic

Maat

Magic

Mantra

Manuals

Meaning

the Media

Mesopotamian Rhetorics

Metaphor

Methodology

Modern Japanese Rhetorics

Modern Standardized Japanese

Moksha/Mokṣa

Multimodal Rhetorics

Mythology

Native American Rhetorics

Natyashastra/Nāṭyaśāstra

Near Eastern Rhetorics

Nelson Mandela

Nommo

Nyaya/Nyāya

the Other

Oral Literacies

Oratory

Othering

Pathos

Pedagogy of World Rhetorics

Performance

Persuasion

Philosophy

Place

Plato

Pluralistic Rhetorics

Poetics

Political Rhetorics

Popular Culture

Post-apartheid Rhetorics

Post-colonial Rhetorics

Post-Mao Rhetorics

Power

Pragmatism

Racism

Ramayana/Rāmāyaṇa

Rasa

Recontextualization

Register

Religious Rhetorics

Repetition

Representation

Resistance

Rhetorical Education

Rhetorical Figures

Rhetorical Histories

Rhetorical Silence

Rhetorical Theory

Rhetorical Traditions

Ritual

Sadharanikaran/Sādharaṇikaraṇ

Sanskrit Rhetorics

Sanskrit Stylistics

Second Language

Shankara/Śaṅkara

South African Rhetorics

Speeches

Spiritual Rhetorics

Storytelling

Subaltern Literacies

Subject Positions

Survivance

Textbooks

Thick Description

Translation

Transnational Rhetorics

Truth

Uchi-soto

Vedic Rhetorics

Vernacular Rhetorics

Visual Rhetorics

West African Rhetorics

Wisdom

Women’s Rhetorics

Worldview

Writing Studies

Endnotes

- Standing Groups of the Conference on College Composition and Communication are membership-driven groups focused around a common interest. They differ from Special Interest Groups (SIGs) in that they have an ongoing organizational status, adhere to a set of bylaws, conduct elections, and report annual updates and accomplishments to the CCCC leadership. return

- WikiProject Writing is an initiative sponsored by the CCCC Task Force on Wikipedia. It aims to improve and increase Wikipedia’s content coverage of “writing research and pedagogy as they encompass broad and evolving definitions of literacy, communication, rhetoric, and writing (including multimodal discourse, digital communication, and diverse language practices),” with a special emphasis on drawing from the scholarship and activism of marginalized teacher-scholars (“Wikipedia:WikiProject Writing”). return

- Robert T. Oliver’s book (now dated) is one example of foundational and persistent scholarship. While scholarship on Chinese and Indian rhetorics is available, some specialties within these traditions are still not widely studied. Newcomers to those specialties will need more substantive information than they might find in the passing references of recent scholarship. return

- Rhetorics that emerge in cultural, linguistic, and political contexts in the Middle East more broadly offer us an opportunity to study the intellectual life that lead to the development of Arabic rhetorical tradition, but also offer us an opportunity to examine how the tradition has been defined and subsequently left out of the West’s scholarly tradition (Borrowman 98). return

- A similar thought process informed our delineation of “Near Eastern” to include Mesopotamia and the Ancient Near East, conflating past and present classifications, and frustrating a clear separation of linguistic value from political identification. return

- Anything less would foreground the merely incidental, causing us to revert to familiar signs of persuasion or argumentation, a warning first sounded by Robert T. Oliver in 1971 (261), and oft cited in recent years as the exploration of rhetorics beyond the West has grown. Incidentally, The process of compiling tags was no less collaborative than the process of annotating the bibliography. We invited contributors to supply their own tags and then we curated the final list. return

- We acknowledge that both lists—our navigational categories and our tags—should be received as fluid and malleable reflections of the field, and we welcome the possibility of making alterations on future iterations of this Annotated Bibliography. return

Works Cited

Baca, Damián, and Victor Villanueva, eds. Rhetorics of the Americas. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2010.

Blake, Cecil. The African Origins of Rhetoric. Routledge, 2009.

Borrowman, Shane. “Recovering the Arabic Aristotle: Ibn Sina and Ibn Rushd on the Logic of Civic and Poetic Discourse.” Rhetoric in the Rest of the West, edited by Shane Borrowman, Robert L. Lively, and Marcia Kmetz, Cambridge Scholars, 2010, pp. 97-118.

Borrowman, Shane, Roberta L. Lively, and Marcia Kmetz, eds. Rhetoric in the Rest of the West, Cambridge Scholars, 2010.

Hum, Sue, and Arabella Lyon. “Recent Advances in Comparative Rhetoric.” The Sage Handbook of Rhetorical Studies, edited by Andrea A. Lunsford, Kurt H. Wilson, and Rosa A. Eberly, Sage, 2009, pp. 153–165.

Kennedy, George. Comparative Rhetoric: An Historical and Cross-Cultural Introduction. Oxford UP, 1998.

Khoury, Nicole. “Self-Reflexive Pedagogy: Reading Against the Western Tradition to Teach Global Feminist Rhetorics,” in Lisa Mastrangelo, David Gold, Nicole Khoury, Michael Faris, Rebecca Dingo, Rachel Riedner, Jennifer Wingard, Gesa Kirsch, and Jacqueline Jones Royster. “Changing the Landscape: Feminist Rhetorical Practices: New Horizons for Rhetoric, Composition and Literacy Studies, Five Years Later.” Peitho, vol. 20, no. 2, 2018, pp. 160-97. cfshrc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Coalition_ChangingtheLandscape_20.2.pdf.

Lipson, Carol S. “Ancient Egyptian Rhetoric: It All Comes Down to Maat.” Rhetoric Before and Beyond the Greeks, edited by Carol S. Lipson and Roberta A. Binkley, State U of New York P, 2004, pp. 79–98.

Lipson, Carol S. “Introduction.” Ancient Non-Greek Rhetorics, edited by Carol S. Lipson and Roberta A. Binkley, Parlor, 2009.

Lipson, Carol S., and Roberta Binkley, eds. Ancient Non-Greek Rhetorics. Parlor, 2009.

—. Rhetoric Before and Beyond the Greeks, State U of NY P, 2004.

Lyon, Arabella. “Tricky Words: Rhetoric and Comparative.” Rhetoric Review, vol. 34, no. 3, 2015, pp. 243-46.

Mao, LuMing. “Beyond Bias, Binary, and Border: Mapping Out the Future of Comparative Rhetoric.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 43, no. 3, pp. 209-25.

Mao, LuMing. ‘‘Reflective Encounters: Illustrating Comparative Rhetoric.’’ Style, vol. 37, no. 4, 2003, pp. 401–425.

Mao, LuMing, et al, “Symposium: Manifesting a Future for Comparative Rhetoric,” Rhetoric Review 34, no. 3 (2015): 239–74.

Mao, LuMing, and Bo Wang. Introduction: Bring the Game On. “Symposium: Manifesting a Future for Comparative Rhetoric,” Rhetoric Review 34, no. 3 (2015): 239-43.

Oliver, Robert T. Communication and Culture in Ancient India and China. Syracuse UP, 1971.

O’Malley, John W. “‘Not For Ourselves Alone’: Rhetorical Education in the Jesuit Mode with Five Bullet Points for Today.” Conversations on Jesuit Higher Education 43, no. 4 (2013): 1–5.

“Wikipedia:WikiProject Writing.” Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, 8 Mar. 2021, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:WikiProject_Writing. Accessed 15 Mar. 2021.

COVER IMAGE CREDIT: Stupa (Storage Place for Holy Relics) by Matt Cox.

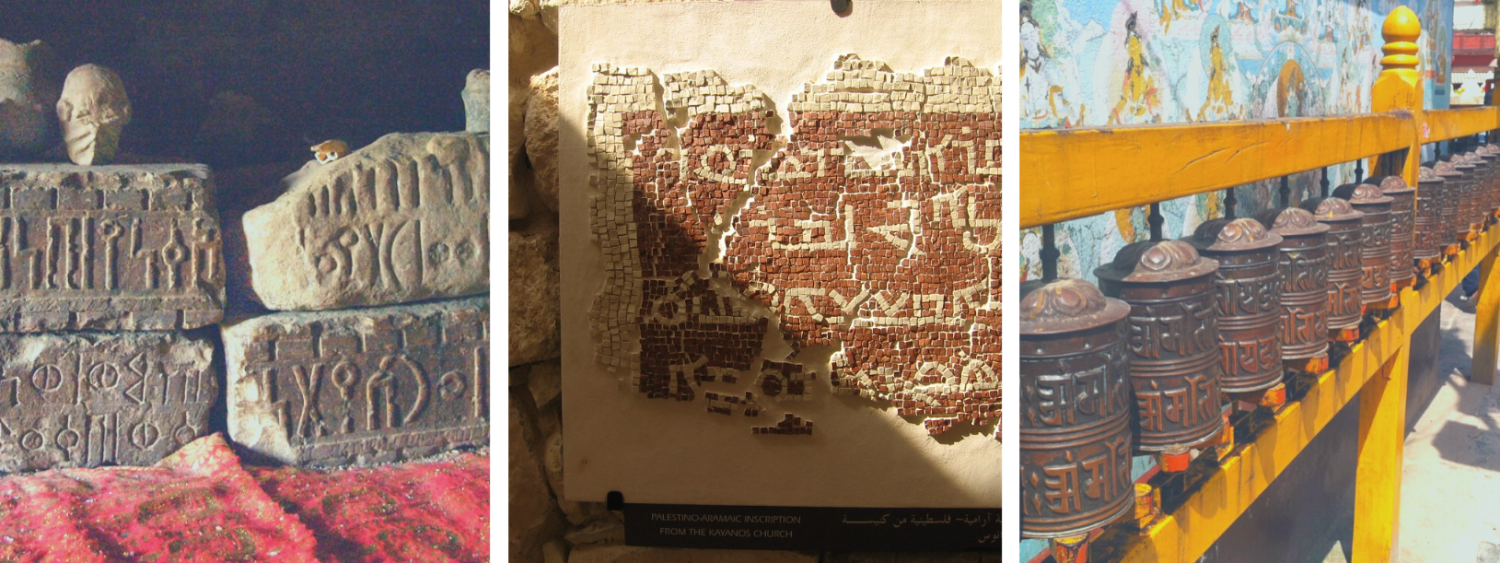

LEAD IMAGE CREDIT: Photo 1 (left): Ancient Ethiopian blocks. “Ancient Blocks With Sabaean Inscriptions, Yeha, Ethiopia” by A.Davey is licensed under CC BY 2.0. Photo 2 (middle): Palestino-Aramaic Mosaic. “ancient language…” by Abouid is licensed under CC BY 2.0. Photo 3 (right): Prayer Wheels with Sanskrit by Matt Cox.

Introductory Overviews

Kennedy, George A. Comparative Rhetoric: An Historical and Cross-Cultural Introduction. Oxford UP, 1998.

In this foundational text, George Kennedy does for comparative rhetoric what Joseph Campbell did for comparative mythology: turned an area of research into a viable field of study. The endeavor and goal of his book is ambitious, in that Kennedy details four objectives that constitute comparative research: (1) discovering what is universal/exotic about a culture’s rhetorical tradition, (2) theorizing about the “deep rhetoric” that informs all instantiations of rhetorical expression, (3) developing a cross-cultural lexicon for categorizing rhetorical phenomena, and (4) expanding our understanding of how to apply comparative findings to our contemporary understanding of cross-cultural communication. Kennedy seeks to reimagine rhetoric as an energy transmitted through speech and text. In developing a cross-cultural lexicon for the study of rhetoric, he primarily applies Western rhetorical terms to non-Western cultures. Though this aids Western audiences in their understanding of the unfamiliar, many have critiqued this traditional approach as being problematic.

The book begins in an unusual way, with an introduction to the rhetoric of animals, before moving to pre-rhetoric and the development of human language. Kennedy’s premise is that, as culture and civilization develop, the relationship between rhetoric, myth-making and magic becomes more complex, with examples from Australian Aboriginal culture. Next, Kennedy addresses the rise of formal speech in non-literate cultures, such as those found in isolated pockets of Africa, the Americas, Asia, and the many island cultures situated in regions of the Indian and Pacific oceans. Investigating the rhetoric of the native Americas, he provides a look into Native American and Aztec rhetorical traditions. In the second half of the book, Kennedy describes rhetoric in literate societies, giving overviews of the rhetorical traditions of the Ancient Near East (i.e., Mesopotamia, Egypt, and Israel), Ancient China, Ancient India, and Ancient Greece and Rome.

Kennedy’s compendium demonstrates an important point about rhetoric itself: cultural practices like myth-making, magic, philosophy, and religion, poetry and literature all occur at the intersection of rhetorical studies. While this book is more widely known as a survey of ancient rhetorics, it is also a comprehensive rhetorical handbook, covering many of the basics of rhetorical thought and terminology for the instructor and student of rhetorical studies.

Tags: Ancient Rhetorics, Chinese Rhetorics, Comparative Rhetoric, Cross-cultural Rhetorics, Historiography, Indian Rhetorics, Magic, Mesopotamian Rhetorics, Methodology, Native American Rhetorics, Near Eastern Rhetorics, Philosophy, Religious Rhetorics, Rhetorical Theory

Lipson, Carol S., and Roberta A. Binkley, editors. Ancient Non-Greek Rhetorics. Parlor P, 2009.

The essays in this collection explore a rich and varied array of ancient rhetorical cultures of the Middle East, the Far East, South Asia, and the land that became Ireland. The editors did not attempt to represent all cultures, but rather to develop the field of study of rhetorical traditions beyond the Greco-Roman-based paradigm which dominates Western rhetorical scholarship. The authors of each chapter consider how particular texts are rhetorical, how they function rhetorically within the cultures that produced them, and/or how those texts shed light on the rhetorical cultures the chapters explore. The discussions prompt reflection on how rhetoric manifested differently around the world in ways that have been unaccounted for in our mainstream histories.

The volume exposes gaps in the knowledge of world rhetorics, raises probing questions, and invites comparative rhetoricians to look for rhetoric beyond the discursive. Evident in these chapters are such concerns as the attainment of moksha, magic, ritual, tombs, and prophecy, in addition to argumentation. The collection points toward the unknown and the unfamiliar and marks a distinct turn in our discipline toward more inclusive and diverse histories. This turn calls for the cultivation of new theories of rhetoric and methodologies for its study, particularly for comparative rhetoric, Lipson writes in her introduction. She problematizes the moniker “comparative” rhetoric as a name for this field of study and instead favors “cultural rhetorics” and talks in terms of “rhetorical cultures,” since comparative methodology can be counterproductive in studies where an emic approach would prove more accurate and fruitful (3-5). This is an important text for scholars embarking upon “comparative rhetoric” research, ancient or contemporary.

Tags: Ancient Rhetorics, Celtic Rhetorics, Chinese Rhetorics, Comparative Rhetoric, Cultural Rhetorics, Dao/Tao, Egyptian Rhetorics, Historiography, Indian Rhetorics, Japanese Rhetorics, Jewish Rhetorics, Magic, Mesopotamian Rhetorics, Methodology, Moksha/Mokṣa, Near Eastern Rhetorics, Prophecy, Ramayana/Rāmāyaṇa, Ritual, Shankara/Śaṅkara

Lipson, Carol S., and Roberta A. Binkley, editors. Rhetoric Before and Beyond the Greeks. SUNY P, 2004.

This collection of essays, compiled by editors Carol S. Lipson and Roberta A. Binkley, follows in the tradition of George A. Kennedy’s Comparative Rhetoric, making a case for revising the history of rhetoric to include other diverse cultural traditions. The book continues to foreground comparative rhetoric as a significant sub-field in rhetorical studies. One caveat is that a lot of the focus continues to be on emphasizing the “before” more than the “beyond.” It includes rhetorical traditions from Mesopotamia, Egypt, China, and the Near East, not only making a case for the study and inclusion of other cultures but also for alternative traditions existing within the same culture, issues of gender representation, the dynamics of mainstream versus peripheral, and challenging the association of rhetoric solely with democratic ideologies.

The editors and authors also emphasize the need for collaboration across other fields outside of rhetorical studies to engage and develop cross-cultural studies such as these, and many of the authors in this volume belong to different disciplines. They acknowledge that issues of conjecture are still needed, such as developing comparative methodologies, using universal/particular terminology, and text translation. The premise of much of the work addresses the need to expand our understanding of rhetoric as a culturally situated practice, meaning that it has its own unique manifestations in each and every culture.

The collection starts with Hallo, who takes the reader to the birthplace of rhetoric in Mesopotamia, exploring the rhetorical genres and conventions of wisdom literature and the epic. Next, Binkley recovers the Mesopotamian poet Enheduanna, preserving the voice of the ancient female rhetor through the genre of the hymn. And Hoskisson and Boswell research the Assyrian annals, making a case for the annal as its own particular kind of rhetorical genre situated between historical fact and narrative, usually relying on an unstated conclusion.

Moving to Egyptian rhetoric, Lipson looks at the genre of the letter and the concept of Maat or “rightness.” In addition, Sweeney seeks to present more of the everyday rhetorical practices of Egypt by examining legal texts.

Transitioning to Chinese rhetoric, Xu focuses on the Confucian perspective by examining the concepts of li (rites), ren (virtues), and yi (righteousness) and the gradations of speech, from silence to superior speech to clever talk. Lyon continues with the Confucian tradition, examining the themes of silence and jian (remonstration), that is, to make objections in respect and trust, enabling the audience to decide for themselves. Moreover, Liu argues that Chinese rhetoric is not a by-product of the philosophical tradition; the philosophical tradition and its figures are Chinese rhetorical criticism.

Turning to the Biblical tradition, Metzger surveys the scribal schools who composed the Pentateuch, covering both the “documentary hypothesis” and the priestly tradition as ways of rereading the socio-political motives behind the construction of the text, featuring the Aaronidic voice as the rhetorical influence that shaped the arc of the Pentateuchal narrative.

Moving to Greece, Enos proposes an alternative rhetorical perspective in contrast to the Athenian one, exploring the rhetoric of Rhodes, differentiating it by its trade culture, diverse socio-political orientation, and its emphasis on cross-cultural communication.

Watts, in a more general sense, surveys ancient Near Eastern texts across Eurasia and Africa, focusing on the cross-cultural story-list-sanction formula, advocating that this universal, rhetorical pattern recounts the narrative past, provides directions for the present, and admonishes blessings/curses for the future. Likewise, applying an emic-etic approach, Swearingen recovers the genre of lamentations authored by female figures in the ancient Near East, examining the woman’s role in ceremonial rhetoric.

What sets this collection apart is its emphasis on making the study of comparative rhetoric accessible for the classroom. The book closes with a “Suggestions for Teaching Ancient Rhetorics,” where each contributor returns to the impetus of their work to give an addendum in the form of suggestions for course design, assignments, and further reading. This focus directs attention to the question: “How can we incorporate comparative rhetoric into our curriculums?” Rhetoric Before and Beyond the Greeks details the broader picture of the historiography of rhetoric for study and scholarship.

Tags: Ancient Rhetorics, Biblical Rhetorics, Chinese Rhetorics, Confucius, Cross-cultural Rhetorics, Egyptian Rhetorics, Epics, Feminist Rhetorics, Genres, Historiography, Jewish Rhetorics, Mesopotamian Rhetorics, Methodology, Near Eastern Rhetorics, Pedagogy of World Rhetorics, Persuasion, Political Rhetorics, Rhetorical Histories, Rhetorical Traditions

Oliver, Robert T. Communication and Culture in Ancient India and China. Syracuse UP, 1971.

With this book Oliver pioneers the study of Eastern rhetorical culture and urges scholars to study them on the cultures’ own terms (261). For Oliver, rhetoric is inseparable from the culture it inhabits, so scholars must examine rhetoric in relation to the philosophy and social customs of the culture (x). He argues that if we look for Western concepts of rhetoric in Asian cultures, then we will not find them; because they are expressions of Western culture, they make sense only in the context of that cultural milieu. Moreover, such a lens tends to render invisible what counts as rhetoric from the perspective of the Eastern culture so that a scholar exploring it might “conclude there is no rhetoric at all” (261). The Western brand of rhetoric is not a universal, Oliver argues. He asserts that the feature of rhetoric common to all civilizations is our ability to “symbolize and to communicate” in ways that allow us to live together (2). So that is where Oliver must start his endeavor.

He posits that the dominant Western culture has separated rhetoric from other ways of thinking and made it a distinct discipline due to a penchant for analysis and division, while by contrast, Eastern cultures do not explicitly distinguish and theorize rhetoric as a discipline because they tend towards a holistic worldview (10). Thus, for Oliver, “The problem is not to find the rhetoric of the East but to find ways of identifying and depicting it in a fashion that will make it meaningful to Western minds without thereby denying its essentially holistic character” (11). To do this, Oliver examines some of the important texts in the cultures he considers along with cultural and historical contextual information and considers how these sources shed light on the rhetorical practices embedded in Eastern worldviews and ways of living.

Oliver concludes that Asian approaches to discourse and communication focused not on the benefit of the individual but on the promotion of harmony; they valued patterns of behavior, ceremonial discourse, silence, and proofs based on authority and analogy (261–264). His effort serves as an important introduction to comparative rhetoric because he articulates the problems of a Western stance toward Asian rhetorics and proposes some heuristics for further explorations. His work holds an important place in the development of comparative rhetorical studies and is justly cited as a groundbreaking work, and a necessary part of any literature review for such studies.

Notably, Oliver admits to the shortcomings of his efforts and invites further inquiry into the rhetorics of the East in hopes that “the very shortcomings of this study will have the effect of encouraging others to follow through and do better what has here been commenced” (xii). Oliver thus not only inspires the young field of comparative rhetoric, but also invites critique. Comparatist scholars have taken up the challenge.

LuMing Mao, for example, has criticized Oliver’s use of secondary (Western) sources, such as accounts by Jesuit missionaries, and questionable translations (see “Reflective Encounters: Illustrating Comparative Rhetoric” in this annotated bibliography [hyperlink]). Oliver used the resources he had at hand to open a new and difficult conversation and challenge Western universals about rhetoric. Those better equipped with the necessary foreign language skills, insider cultural experience, and access to primary sources can respond to and move beyond this book to correct Western misconceptions and build knowledge about particular Eastern rhetorical cultures.

Tags: Analogy, Chinese Rhetorics, Communication Theory, Comparative Rhetoric, Consensus, Indian Rhetorics, Methodology, Worldview

Methodologies

Alcoff, Linda. “The Problem of Speaking for Others.” Cultural Critique, vol. 20, Winter 1991-1992, pp. 5-32. JSTOR, doi:10.2307/1354221.

Linda Alcoff begins this article by asking if the practice of speaking for others, especially those less privileged, can ever be valid. She centers her interrogation of this question around the location of speaking. While location impacts meaning, it cannot determine it. Location, she writes, is not a fixed essence and thus meaning cannot easily be evaluated in terms of a speaker’s location, their connection to structures of power, or the resulting politics that surround speech. This reality is further highlighted as Alcoff explains why retreat is an inadequate response to the problem of speaking for others. Retreat assumes that one can only speak for the self, idealizing error-free speech and ignoring effects. She encourages dialogue, or Gayatri Spivak’s “speaking to” instead. And, ultimately, she suggests that the dangers of speaking for others can be curtailed by critical awareness.

To encourage such critical awareness, she makes four concluding suggestions for those who might speak for others: (1) recognize the desire to speak as an attempt at mastery, first, and to resist this impulse, (2) interrogate your own location with the help of others in order to understand its impact on our speech, (3) remain open to criticism and occupy a position of accountability, and (4) attend to the effects of your speech and its impact on content. Effect matters most for Alcoff in the end. Location, she argues, matters only inasmuch as it determines effect. Rather than focusing on who is speaking for the oppressed, then, she suggests that we must understand how an act of speaking empowers or disempowers oppressed people.

Tags: Cross-cultural Rhetorics, Dialogue, Meaning, Methodology, Power, The Other, Representation

Baca, Damián. “Rethinking Composition, 500 Years Later.” Journal of Advanced Composition, vol. 29, no. 1/2, 2009, pp. 229-242. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20866892.

Baca argues that now, five hundred years after Europe’s colonization of the Americas and its campaign of “reinventing the cultural Other” in European terms (230), the time is ripe to recognize and restore the dignity and the sophistication of ancient Mesoamerican multi-modal composition practices. He argues that the pictographic literacies by which they “ordered their world” were not “insufficient” or inferior to alphabetic composition imposed by the conquerors in order to civilize and improve them, but instead were “complex and equally suitable tools of literacy” (230), tools which have once again become current in the internet age (234). He posits that this re-ascendance of multi-modal composition is due to the need for “the introduction of ‘new’ mechanisms of handling information. . . . A main feature of globalized software is the ability of adjustment to different media—ideograms, logograms, iconography, pictograms, and competing alphabets” (234). This new development, Baca asserts, should inspire new appreciation for actually very old composition systems and cultures.

Placing the dawn of globalization at 1492, Baca argues for a “new” understanding of composition to account “for both alphabetic and non-alphabetic properties of Mexican activity,” a view of composition which also responds to other “peripheral, non-Western inscription systems around the globe” (237). In Mesoamerica, for example, in contrast to the Roman alphabet, “writing is virtually synonymous with the sacred . . . a result of divine providence” (237). Thus one cannot assume that Western technologies of globalization need necessarily constitute Westernization, because local form, content, and culture use the “technologies that potentially resume historical trajectories” of their own (237).

Baca asserts that new ways of writing history invite not only revisionist histories but also the rethinking of composition from Mexican legacies in ways that reverse “the enduring Aristotelian syndrome of marginalizing and subalternizing those forced into an occupied periphery by a vanguard global center” (239). Finally, Baca proposes that looking at composition from a Mexican perspective can serve as an intervention into the current politics of writing instruction and give a greater understanding of “parallel writing systems and rationalities” in America (239).

Tags: Colonial Rhetorics, Divinity of Speech, Historiography, Indigenous Rhetorics, Multimodal Rhetorics, Native American Rhetorics, The Other, Poetics, Rhetorical Histories, Rhetorical Traditions, Visual Rhetorics

Bizzell, Patricia, and Susan Jarratt. “Rhetorical Traditions, Pluralized Canons, Relevant History, and Other Disputed Terms: A Report from the History of Rhetoric Discussion Groups at the ARS Conference.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 34, no. 3, Summer 2004, pp. 19-25. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40232430.

Patricia Bizzell and Susan Jarratt report on a conversation at the Alliance of Rhetoric Societies meeting, debating the viability of a singular “rhetorical tradition.” Conducted within two smaller working groups, the ARS debate drew attention to both rhetoric and tradition as disputed terms, which all participants agreed were in need of some level of pluralization, and they offered some metaphors as substitutes for tradition, including inventory, constellation, and frame.

However, the primary inquiry of the deliberation at the ARS meeting revolved around how to research and teach rhetoric as rhetorics, looking at the following models: (1) multicultural, (2) dominance/resistance, (3) comparative, (4) bracketing, (5) transnational, and (6) refiguring. Bizzell and Jarratt report that, during conversation, there was hesitation and difference among deliberators as to whether it was necessary to provide an indigenous term or to borrow “rhetoric” as the defining term for classifying a particular cultural practice.

Another question central to this debate was “Why teach the history of rhetoric in the first place?” Participants responded by emphasizing the importance of recognizing diversity and integrating marginalized rhetoricians, rhetors, and texts. They also argued for the need to address issues of citizenship, democratic values, and the writing of history itself as integral to answering the question.

Tags: Citizenship, Democratic Rhetorics, Historiography, Methodology, Pedagogy of World Rhetorics, Rhetorical Histories, Rhetorical Traditions

Cummings, Lance. “Comparison as a Mode of Inquiry: Rearticulating the Contexts of Intercultural Communication.” Rhetoric, Professional Communication, and Globalization, vol. 5, no. 1, Feb. 2014, pp. 126–46.

In response to the global turn in English studies, Cummings rearticulates the act of comparison as a mode of inquiry, rather than a way to categorize or collate difference. After giving a brief overview of different comparative methodologies in English studies, Cummings shows how comparison has created sedimentations, or calcified ways of thinking, that often reify or reinforce old ways of seeing and the power structures they support (128). These sedimentations are often invisible when we approach comparison or build cross-cultural texts, which he illustrates through the analysis of Web 2.0 learning spaces and qualitative research with international students. In the end, Cummings argues for an approach to comparison that seeks to un-sediment habits of thought by deeply reflecting on the context of comparison and adapting our methodologies to reveal and rearticulate how we see rhetoric and writing across cultures.

Tags: Comparative Rhetoric, Cross-cultural Rhetorics, Intercultural Communication, Methodology

Dingo, Rebecca. “Linking Transnational Logics: Feminist Rhetorical Analysis of Public Policy Networks.” College English, vol. 70, no. 5, 2008, pp. 490–505. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/25472285.

In this article, Rebecca Dingo analyzes the networking of United States welfare policies and World Bank development policies to understand the neoliberal market’s effect on women across the globe. Her feminist rhetorical analysis demonstrates how domestic and international policies are linked in ways that paternalistically and incongruously maintain gender norms. For instance, while US welfare policies encourage single mothers to marry, World Bank policies emancipate women from the home by bringing them into the marketplace as financially independent entrepreneurs.

Despite their contradictory emphases on family and independence, these policies follow a logic determined by capitalism that places the responsibility of the family’s success on women. Dingo reveals, in particular, how this policy of “mainstreaming women” emerges from the perception that women will generally place the well-being of family above their own. This policy, for Dingo, shows how the World Bank fits into a narrative of economic development determined by wealthy nations like the US.

These economic reforms seek to transform culture but disregard cultural context in favor of the market, Dingo posits. Conundrums like childcare, however, reveal this faulty logic and its disregard for class and the material outcomes of such policies. Therefore, Dingo argues, it is essential that the field of feminist rhetorical studies juxtapose transnational texts to understand the complex connections between national and international policies.

Tags: Feminist Rhetorics, Political Rhetorics, Transnational Rhetorics

Enos, Richard Leo. “On the Trail of Ancient Rhetoric: Fieldwork of a Wandering Rhetorician.” Advances in the History of Rhetoric, vol. 6, no. 1, 2012, pp. 43-51. Taylor & Francis, doi:10.1080/15362426.2001.10500535.

Commenting on rhetorical studies’ strong reliance on verbal (or discursive) texts as its subjects of analysis, Richard Enos launches a critique against the field’s exclusive emphasis on traditional forms of historical evidence—books and other literary sources—in our rhetorical theories and histories (43). In order to better contemplate the future of rhetoric, Enos advocates for the inclusion of non-discursive historical sources to “exponentially increase our repository of evidence” to enrich our rhetorical perspectives (44). In response to this charge, Enos extols the value of fieldwork in rhetorical studies. This essay offers a four-step procedure for fieldwork: “1) isolating research sites, 2) securing permission prior to investigation, 3) collecting on-site data, and 4) research objectives after returning from fieldwork” (46). Enos’ methodological approach to fieldwork holds important implications for scholars in comparative rhetoric who aim to study rhetoric in places and cultures where discursive or literary evidence has not been recovered.

Tags: Archaeology, Fieldwork, Historiography, Methodology

Enos, Richard Leo. “Rhetorical Archaeology: Established Resources, Methodological Tools, and Basic Research Methods.” The SAGE Handbook of Rhetorical Studies, edited by Andrea A. Lunsford, Kirt H. Wilson, and Rosa A. Eberly, Sage Publications Inc., 2009, pp. 35-52.

Richard Enos notes that a rhetorician’s job is not only to teach but also to discover and create new knowledge for teaching. In defense of rhetorical research, he aims to establish a relationship among resources, research, and methods. Concerned with the scope of the rhetorical tradition and using archeology as an analogy, Enos advocates for a “rhetorical archeology,” arguing that “both our secondary research and the retrieval of new, primary resources is incomplete” and that in order to “fully appreciate and be sensitive to rhetoric, one must understand context—in this case historical context” (40). He provides readers with guidance on how to engage in primary research in the field of rhetoric by reviewing several well-established historiographies, while acknowledging that such works are interpretations motivated by particular historians’ objectives.

Enos also examines speciality and thematic studies, such as Walter Ong’s work on the relationship between orality and literacy or Eric Havelock’s work on the relationship between oral and written expression, which Enos claims, for example, shows the importance of “sensitivity” to understanding “how mentalities operate differently in non-literate and literate cultures” when researching rhetoric’s history (36). In addition, Enos cites contemporary women rhetoricians (e.g., Andrea Lunsford, Cheryl Glenn) whose works are valuable resources for gender-related and other rhetorical historiographies. He then discusses the procedures for archeological fieldwork in rhetoric (e.g., how to secure archival permission).

Overall, for more comprehensive accounts of a rhetorical tradition, Enos overviews two important phases of rhetorical research. The first phase is fieldwork using archeological research methods. The second is to “reconstruct an artifact by employing the heuristics of rhetorical layering,” which consists of four interactive strata of analysis: “discovering the social, political, and cultural conditions; reconstructing the rhetorical situation or kairos that induces discourse; analyzing the actual discourse; and finally, displaying of this work in a manner that reconstructs the dynamic interaction of these layers” (57). The rhetorician can then choose the most sensitive heuristics to analyze discourse or theory and “explicate the event for public display” (57).

Tags: Feminist Rhetorics, Fieldwork, Historiography, Methodology, Oral Literacies, Rhetorical Theory

Enos, Richard Leo. “Theory, Validity, and the Historiography of Classical Rhetoric: A Discussion of Archaeological Rhetoric.” Theorizing Histories of Rhetoric, edited by Michelle Ballif, Southern Illinois UP, 2013, pp. 8–24.

In this chapter, Richard Enos launches a critique against the discipline’s inattention to matters of historical context, archaeological evidence, and nonliterary forms of evidence in our histories of rhetoric (9). Such orientations to traditional historical research can be reconfigured, Enos suggests, should we accept the invitation to seek out new historical methods and atypical forms of historical evidence.

Enos recognizes the tremendous potential of borrowing methods from Archaeology and adapting those methods for rhetorical studies. Fieldwork, he suggests, can allow rhetoricians to study material and nondiscursive forms of evidence that may illuminate new contours of rhetoric not exemplified by discursive or literary evidence alone. According to Enos, archaeological rhetoric can “reveal the mentalities driving ancient rhetoric” (13). Put simply, the adaptation of archaeological methods to rhetorical studies can enable comparative rhetoricians to develop more robust understandings of the social, cultural, and historical contexts that influenced how rhetoric emerged in antiquity. Archaeological evidence is especially critical for those comparative rhetoricians who want to learn about global rhetorics in places where traditional forms of literary evidence have not been found.

Tags: Archaeology, Fieldwork, Historiography, Methodology, Rhetorical Histories

Fatima, Saba. “Muslim-American Scripts.” Hypatia, vol. 28., no. 2, Spring 2013, pp. 341–59. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24542125.

This article offers a theoretical assist to scholars of Muslim Americans’ diasporic texts. Fatima’s uptake of “script” helps identify and then critique the implicit expectations that diasporic communities—namely, Muslims residing in the United States—must demonstrate a kind of patriotism in order to be rhetorically and epistemically understood as belonging. This is in part due to an expectation that all immigrants are expected to align with US foreign policy; however, it is also partly due to the “idea of Muslims being one entity, one nation, an ummah, which is a normatively prescribed notion within the Islamic faith” (346).

In the same way that not all Muslim-Americans have diasporic ties to extremist groups or even to the same notion of “Islamic nation” (346), their testimonies may be subject to the same type of distortions—“unreflectively and nondoxastically”—that Fatima says occurs through the lens of Muslim Americans’ “perceived loyalties and values” (347). In pushing for a more empathetic Muslim epistemology, Fatima asks Muslim Americans to “confront our affinities, our loyalties, and our values as resources of knowledge to better inform our participation in American politics” (352). Only then, she argues, will such an identification such as “Muslim American” lead to an appropriate epistemology.

While her study principally considers discourse in the United States, the essay’s central claim—“that our complex affective response can inform our social and political discourse in a more morally adequate and responsive way” (343)—makes the concept malleable for rhetorical study of localized diasporic communities in other parts of the world. It does so by offering scholars a way to think about scripts not only as semantic containers, but also as collections of concepts or ideas related to a particular discursive event. It also does so by helping scholars to understand what makes their projects political even if they don’t explicitly involve politics.

Ultimately, Fatima argues that, if we know how to look for them, “scripts” are capable of expressing incongruities between whole theories of language. Thus, scholars can use scripts to identify and complicate the terms that they typically associate with global rhetorical work (i.e., diaspora and standpoint) so as to do more than just essentialize or reverse-essentialize one cultural group or another.

Tags: Diasporic Rhetorics, Islamic Rhetorics, Methodology, Political Rhetorics

Garrett, Mary M. “Tied to a Tree: Culture and Self-Reflexivity.” Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 43, no. 3, 2013, pp. 243–55. Taylor & Francis, doi:10.1080/02773945.2013.792693.

In her contribution to a special issue on “the Future of Comparative Rhetoric,” Mary Garrett laments that disciplines which require textual interpretation often offer little systematic instruction on how to improve self-reflexivity as a research methodology (243), raising self-awareness of the researcher’s own cultural biases. Yet comparative rhetoric depends heavily on scholars’ self-reflexivity to fairly interpret texts from rhetorical traditions other than their own. She proposes an approach for ameliorating cultural bias by synthesizing methodologies from cultural anthropology, qualitative research, and critical theory. She also consults ethnology, sociology, and feminist theory to derive three practices for enhancing the ‘how’ of comparative rhetoric: “monitoring one’s responses, asking the ‘natives,’ and putting oneself in the position of the other” (245; 252-254). Toward the first objective, Garrett kept a journal to heighten her awareness of her own responses to the Chinese text she discusses in this essay, aware of the “high stakes” of studying “an emerging area that is still characterized by unequal power relations as well as issues of status and cultural pride” (245).

At the beginning of her essay, Garrett shares the story of how she struggled with a particular Chinese text, the section of the Shishuo xinyu [sic] dealing with “Virtuous Conduct,” and how she strove to overcome her shock at the moral decision which the text presents by attempting to read it from the position of the other (244). Her attempt to place herself in the other’s shoes and thus understand Chinese values and the power dynamic between children and their parents illustrates the problem: Western rhetoric scholars cannot afford to impose their own cultural experience—its privileges, values, and social status—on the texts which often present contrasting socio-historical experience, power relations, and values.

Eurocentricity, Garrett argues, creates an unbalanced power dynamic between the West and China, which hinders Western understanding of Chinese texts. Garrett also calls attention to the complex political relations between the US and China, and China and Taiwan, explaining how the impact of the Cultural Revolution is still in full swing. She gives examples of the imbalance of power dynamics in comparative rhetoric studies, which tend to be conducted through a Western lens. She outlines the debates on self-reflexivity and posits that Western comparatists fail to consider the consequences of unreflective practices. More specifically, in her realization of the many conditions she did not share with the Chinese women whose writings she studied, Garrett located a way of systematically uncovering levels of influence on reading the ‘other’ (249). Ultimately, she posits that the exercise of empathy is an ethical way to conduct comparative rhetoric scholarship by helping scholars attain a better sense of the differences unique to each text (245-250).

Tags: Chinese Rhetorics, Comparative Rhetoric, Ethics, Methodology, The Other, Representation

Geertz, Clifford. The Interpretation of Cultures. Basic Books, 1973.